At 4:30 pm on September 10, 2024, bill AB-1825 was presented to the governor of California, Gavin Newsom. Nineteen days later, the bill was approved, allowing access to books and materials in libraries throughout the state to change indefinitely.

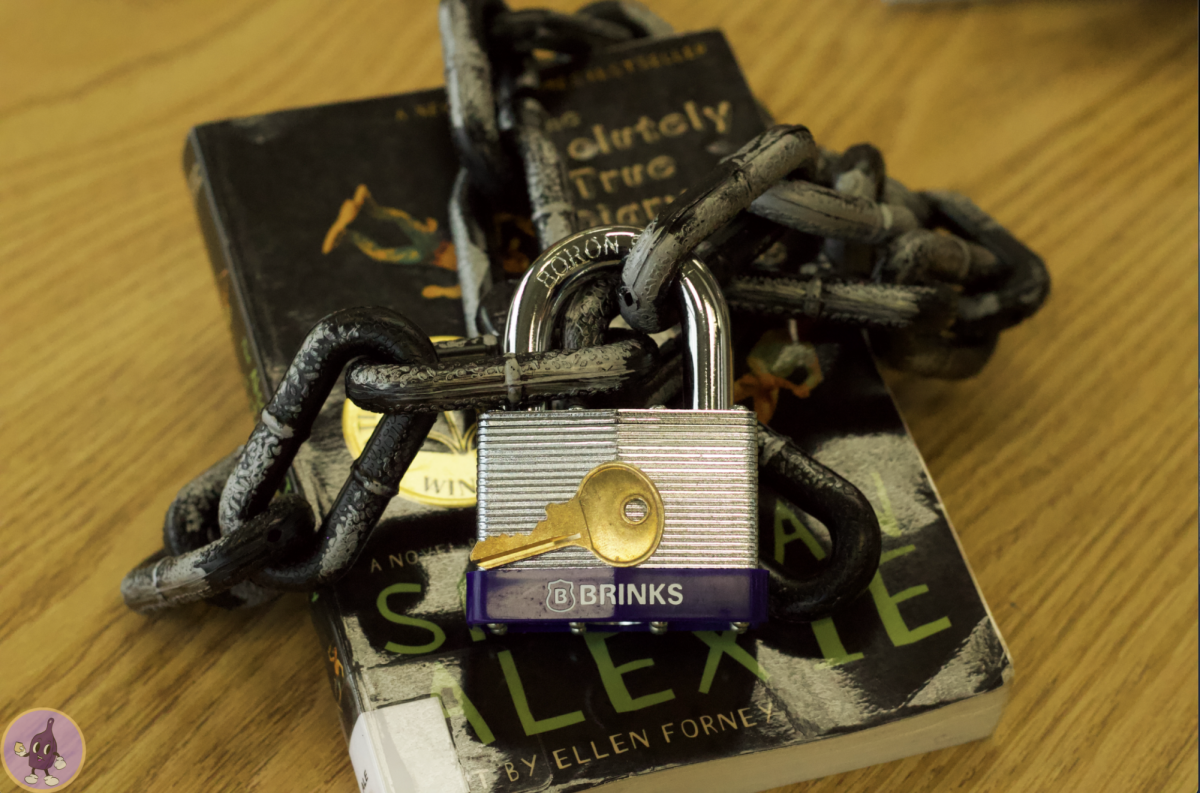

Bill AB-1825 is a bill, penned by Assemblymember Albert Muratsuchi, that protects the removal of books and textbooks from public and school libraries in California. His law proposes that no book or informational text should be removed based on the sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, gender identity, disability, social economic class, politics of the author, intended audience, or the book’s subject.

For California, laws looking to protect the right to freely read are nothing new. In 2023, bill AB-1078 was signed into law. AB-1078 states that all students of any Californian school have equal access to unique material, and to discriminate against a title because of its diverse topics goes against the California law.

This bill protects books and informational text that may contain “taboo” topics, of which BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) and LGBTQ+ perspectives are usually the most common.

In defense of bill AB-1078, First Partner Jennifer Siebel Newsom states, “When we restrict access to books in school that properly reflect our nation’s history and unique voices, we eliminate the mirror in which young people see themselves reflected, and we eradicate the window in which young people can comprehend the unique experiences of others”.

AB-1078 came at a time when the amount of attempted book banning was the highest ever recorded. In 2023, 4,240 individual book titles were challenged across the country, and 47% of those books involved the perspectives of LGBTQ+ and BIPOC people. Some of these titles included The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky, All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, This Book is Gay by Juno Dawson, and most notably Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe, which garnered 106 challenges alone.

LGBTQ+ and BIPOC perspectives are usually most attacked, but material with “explicit” content and profanity are also commonly under fire, especially when they are being taught in schools.

Books that have been considered part of American literature for years have been challenged for explicit content, such as The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, The Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger, and To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee.

At the heart of all these laws and bans is a concern for the safety of children. What children should read, what their maturity levels can withstand, what will damage their development, what goes against their family’s values; these questions are the driving forces for book challenges.

Of the books most recently banned, here are the common reasons:

- sexual content (92.5% percent of books on the list)

- offensive language (61.5%)

- unsuited to age group (49%)

- religious viewpoint (26%)

- LGBTQIA+ content (23.5%)

- violence (19%)

- racism (16.5%)

- use of illegal substances (12.5%)

- “anti-family” content (7%)

- political viewpoint (6.5%)

The individuals concerned about the information their kids are exposed to have been choosing whether to limit it or not. In Fresno, California, adults were faced with this decision at a local library.

The librarians at this Clovis library had set up a Pride Month display of books in the kid’s section, and several guardians were displeased by it. These parents believed that this material was too graphic and mature for young readers, especially those without parental permission.

“We have age limits for movies. We have age limits for alcohol,” Fresno County Supervisor Steve Brandau says about material involving discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity, “And it’s not unreasonable to have age limits on sexually graphic material.”

This dispute occurred at the same time as the signing of bill AB-1078, which immediately shut down talks of developing a material review committee among the parents and leaders in the community.

On the other side of this disagreement, some parents thought banning books based on LGBTQ+ content was harmful to the children; that the perspectives within these texts were important for a kid’s development of empathy and self-identity.

“Somehow in the ‘we need to protect kids’ platform that they have stated, trans kids [and] LGBTQ kids have not been considered part of that population that they need to protect,” says Tracy Bohren, a queer mother of two kids in the community.

That is where the moral discussion lies for librarians and book banners alike; where is the line between harmful and helpful?

Recognizing the time and effort libraries put into honing their craft, some people believe that the librarians who put out these displays know which books are beneficial to children.

“At the center of this bill is the fundamental respect for professionally trained librarians to be making the decisions as to what book titles and how to present them to the general public,” Al Muratsuchi voices.

Who gets to decide what is harmful to children? Nobody has the exact answer, but it could be said that those kids should be able to decide for themselves.

When interviewed about the making of bill AB-1825, Muratsuchi stated that the freedom to read is a “cornerstone of our democracy.”

“Unfortunately, there is a growing movement to ban books nationwide, and this bill will ensure that Californians have access to books that offer diverse perspectives”.

Between January 1st and August 31st of 2024, 1,128 individual book titles have already been challenged. This number is certainly lower than last year’s 1,915 titles in the same time period, which could be due to the protective measures California and other states are taking to limit book bannings. Bill AB-1825 has very recently been signed, so the effect can’t exactly be seen yet.

But, if the acceptance of the new law goes the way Governor Newsom intends it to, kids and adults alike will have the right to access books from any perspective they might like, for the benefit of their own connection and empathy.