The soulful voice of Aretha Franklin. The good vibrations of The Beach Boys. The finesse of Bruno Mars.

What’s something all of these artists have in common? The musicians and engineers who made their songs what they are. Record companies have a long, rich history filled to the brim with stories of conflict and compromise, flooding out in the art that was born within their studio walls. Behind the companies and the stars we’ve come to know and love are the session musicians who put their ideas and skills to work to make the music what it is. Despite the fact that these musicians made history through their work in developing the art (and moving culture forward), they receive little to no recognition for their expertise.

Former studio musician and UM professor John Wicks has years of experience as a studio musician in LA. He describes his experiences as such: the ups and downs of recording, demands, learning curves, and what makes the work all worthwhile.

CREDIT WHERE CREDIT IS DUE

Wicks says that not being credited is something that always bothered him about working as a session musician. This is a common issue among studio musicians, experienced throughout the history of the profession. One example is the “Funk Brothers”, a group of musicians who performed on countless songs throughout their careers. They are known as being a hit machine, yet never received credit for being on records until “What’s Goin On” by Marvin Gaye in 1971 (12 years after they had started with Motown Records).

This record company was known for the soulful sound that went into every album released under its name. The specific Motown sound came from the artists who spent countless hours working together, playing all the time. These men were the sounds behind Stevie Wonder, The Jackson Five, The Temptations, and Smokey Robinson (just to name a few). Although the Funk Brothers were the source of the iconic sound, they received little to no credit for their artistry.

Bassist of the group, James Jamerson, is known for his unique technique of playing while only using one finger to pluck, but still achieving incredible fast riffs. He is to this day considered one of the greatest bassists of all time. After his passing, came in bassist Bob Babbitt. The group also included guitarists Joe Messina, Eddie Willis, Robert White, Pianists Earl Van Dyke, Joe Hunter, and Johnny Grifith, drummers and percussionists, Uriel Jones, Benny Benjamin, Richard “Pistol” Allen, Eddy “Bongo” Brown, and Jack Ashford. These men grew together as musicians and people, protecting each other through economic strife, New York riots, being held at gunpoint… all of this they faced together while making incredible music along the way but receiving no credit.

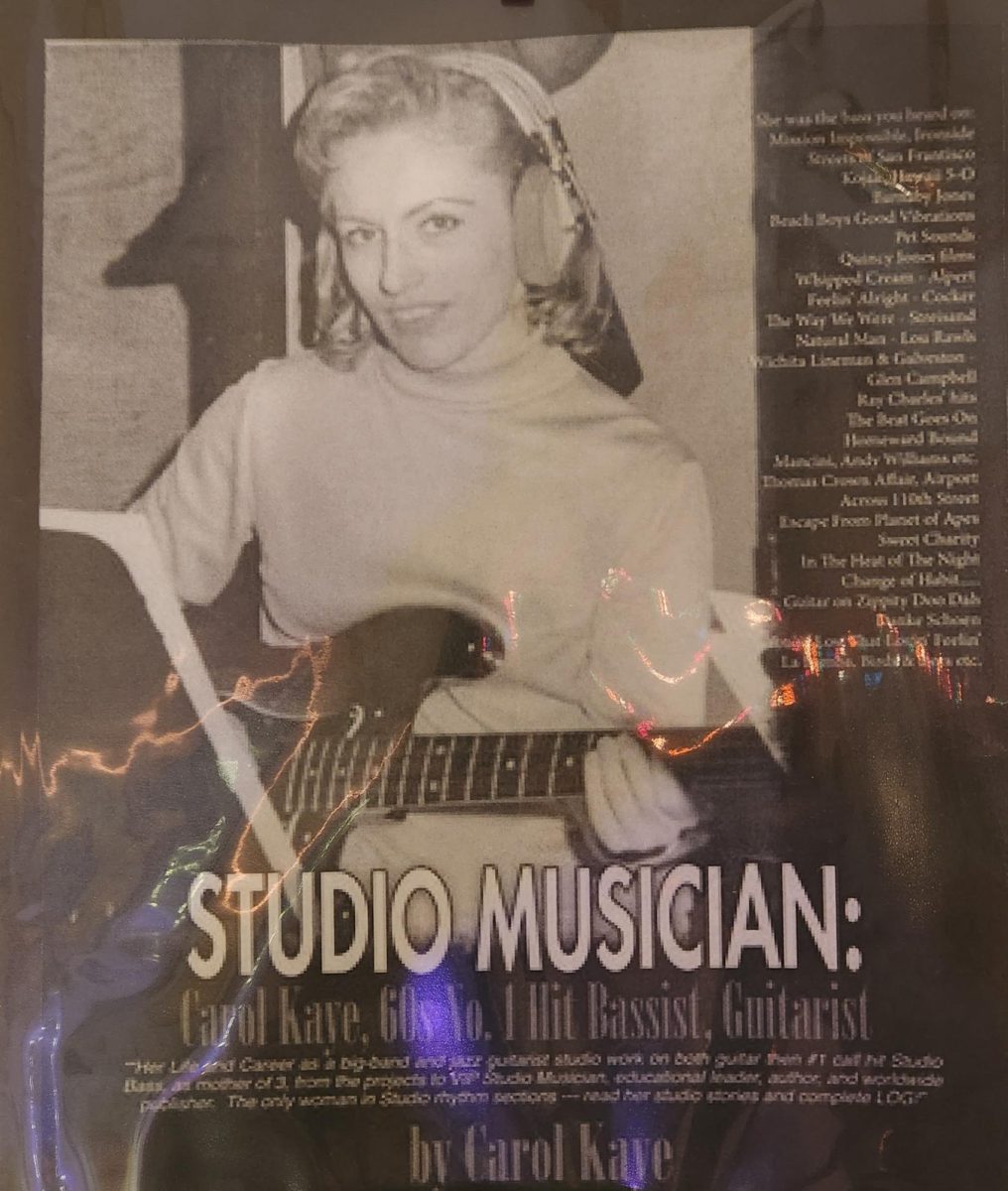

Another group that recorded with many artists and didn’t receive recognition was the “Wrecking Crew”, including lead members Hal Blaine on drums, and guitarist Tommy Tedesco.* This group of musicians recorded with the beach boys among others, but didn’t receive their due credit either. Additional leading member, Bassist Carol Kaye said that this was something that didn’t bother her, but many other musicians did not feel the same.

The Wrecking Crew was well paid for their time, a luxury which the Funk Brothers did not have. Many present-day studios and artists justify uncredited work with financial compensation; however, this has not always been the case. In the ‘60s the pay was so little that the Brothers could no longer afford to only work in the studio. Even though they were recording for 17-hour days at some points, they weren’t making enough to support their families. Despite studio musicians having union representation, many studios paid underneath the union rates. A few of the Funk Brothers went on the road to search for new opportunities and some stayed, playing at live venues in their limited free time (venues that were also stingy with their compensation).

COMPROMISE AND CORRECTION

Wicks detailed another issue faced by session musicians: the demand of the job both in time, skills, and mental taxation. Like many session musicians (including Carole Kaye of the Wrecking Crew and a majority of the Funk Brothers), Wicks started out as a jazz musician. A common theme throughout these musicians is an idea that they had to settle going from jazz to pop music.

While they had to compromise and move from their preferred styles, many of these artists learned to love the new ones. In the transition, however, they had to overcome large learning curves. Wicks described his struggles as a drummer with simplifying the grooves he played and becoming familiar with both new genres and catering to the desires of the recording engineers and artists. **

Along with the demand of learning new styles is the stress of playing (in a timely manner) exactly what the engineers are asking for. There are only so many chances to get the right take, so the pressure these musicians get put under is substantial. The Funk Brothers generally had three chances at most. Especially since they were recording on vinyl, they needed to get everything right as soon as possible.

Wicks stated that session musicians are often referred to as “red light players”, meaning that once that studio recording light goes on they become hyper focused in their playing. Wicks compared this sensation to rock climbing: you know what all of your limbs are doing and where they need to be going, and that’s it. You aren’t thinking about what you ate for lunch, or what movie you want to watch later… just what your body is doing. Nothing else matters in that moment.

The physical demand that comes with the job is only part of the stress. The mental toll that comes with the occupation is just as burdensome. Musicians will often be in the studio constantly with little time for themselves. The Funk Brothers constantly faced this problem. To escape the work they would find hideouts around town – one of these places included a funeral home. They would hide out there and shoot the breeze, but when a Motown lookout would come to bring them back to the studio they had a spiel prepared for the mortician to scare them away. The free time these men had was so limited that they had to hide away to get just a few hours to themselves.

CULMINATION AND ACCOMPLISHMENT

Despite the demands of the job, Wicks described the feeling that makes it all worthwhile. When a musician starts out with their song, plucking it out on a guitar in their bedroom, they can’t predict where it could end up. Revealing the final product, with all of the expertise and vision added, the artists see their ideas come to life in ways they could’ve never imagined.

Although the learning curve is great and the stress is high, Wicks described the excitement and joy that comes when you sit down to start a recording. The adrenaline racing. The collaboration with artists. The final vision. All making the time spent invigorating and wonderful.

Although session musicians have long been underappreciated and unrecognized, their work and their influence on music culture is boundless.

*The wrecking crew is an unofficial group named after their time, but includes musicians Earl Palmer, Barney Kessel, Plas Johnson, Al Casey, Glen Campbell, James Burton, Leon Russell, Larry Knechtel, Jack Nitzsche, Mike Melvoin, Don Randi, Al DeLory, Billy Strange, Howard Roberts, Jerry Cole, Louie Shelton, Mike Deasy, Bill Pitman, Lyle Ritz, Chuck Berghofer, Joe Osborn, Ray Pohlman, Jim Gordon, Chuck Findley, Ollie Mitchell, Lew McCreary, Jay Migliori, Jim Horn, Steve Douglas, Allan Beutler, Roy Caton, and Jackie Kelso in addition to the aforementioned leading members.

**There is a belief held among some drummers, shared with him by a former teacher: Ringo Starr (of the Beatles) was the death of the modern drummer. They believe this because of his simplicity and basic groove. Wicks, however, believes quite the contrary. Ringo set the standard for studio musicians. He was very thoughtful in his playing, filling only when it really added something.

A common issue with drummers is the desire to constantly add to the sounds, and although that is great for some styles, it is less appropriate for others. Starr made it so that the basic groove was set with a very strong feel, and he added what was needed tastefully. Wicks recalls a session when he was asked to play a “Ringo Starr lick” for a recording. This is an example of the great influence he has had on the music industry, so much so that his licks are expected to be known by memory to session drummers.